For specific rates and policies mentioned in this article, it is best to directly consult the service provider's latest official materials, as this information may change over time. Please do not use the data mentioned in this article as a basis for decision-making.

Being ignorant can be blissful, which is what the "curse of knowledge" is all about.

For example, Nikkei Asia tears down iPhones every year. Last year, when they disassembled the iPhone 15, they estimated the component cost at $432. Roughly calculating based on the lowest configuration price of $799, they suggested Apple could make $376 per phone sold.

Although Nikkei doesn't intend to guide public opinion, such calculations, when sensationalized by other media, can turn into claims that Apple, as a capitalist, is making a fortune - selling one phone for nearly the cost of making two. But how could this be possible?

So today, let's discuss how these costs actually break down, perhaps reducing some of our blissful ignorance.

First, it's important to note that in today's market economy, any fee that persists long-term - whether we consider it cheap or expensive - is the result of a trade-off.

Fees for withdrawing from WeChat Wallet and Alipay

Since 2016, withdrawing more than 1000 yuan from WeChat Wallet (where money from WeChat red packets goes) to a bank card or to pay off a credit card incurs a 0.1 yuan fee.

The "over 1000 yuan" is cumulative. If you withdraw 1 yuan 1001 times, the first 1000 times are free, but from the 1001st time, you'll actually receive 0.9 yuan.

Alipay has similar fees for withdrawing to bank cards. You can refer here for details.

Many people think WeChat and Alipay are just trying to make money, arguing that "direct transfers between bank accounts are free." However, transferring from WeChat/Alipay to a bank account is different from transfers between bank accounts and can't be directly compared. To simplify understanding, I've simplified the description, so please excuse any inaccuracies.

Firstly, WeChat's company can't manage money because it's not a bank. The money in WeChat Wallet is actually held in custody in bank accounts. So, you can roughly understand it as Tencent having a bank account where all users' WeChat Wallet funds are kept.

When initiating a withdrawal, what's actually happening is a transfer from Tencent's corporate bank account to the user's personal bank account. At this point, different banks, channels, and times will incur different handling fees. So, "free transfers between personal accounts" doesn't necessarily mean "free transfers from corporate bank accounts."

Since each withdrawal from WeChat Wallet is essentially a corporate bank account transfer, it naturally incurs fees. Passing these fees on to users is completely reasonable - after all, the convenience of WeChat transfers comes at a cost elsewhere, which is a trade-off.

Paying fees for every purchase

Again, using WeChat as an example (Alipay is similar).

First, let's clarify that the wallet in the WeChat app is not part of "WeChat Pay." It's called "Payments and Wallet."

You might ask, then what does "using WeChat Pay" mean when buying things outside? Actually, this phrase refers to the action of "using WeChat to pay for this product."

When a payment occurs, the backend process is quite complex, but there are roughly three scenarios:

- If the shop owner presents a personal WeChat QR code, asking you to add them as a friend and then transfer money: This is essentially a transfer, no different from transfers between friends, and is free.

- If the shop owner presents a WeChat collection code, and scanning it shows their personal avatar, this is very similar to a transfer. Although it can currently be treated as a transfer, this scenario is actually a business activity. It's a payment, but according to my understanding, it doesn't fall under "WeChat Pay."

- If the shop owner presents a WeChat collection code, and scanning it shows the shop name or product name, this is a payment, and in this case, the shop owner is using "WeChat Pay."

In short, WeChat Pay is a product for merchants. If a shop wants customers to pay with WeChat, they need to integrate WeChat Pay, and the shop owner has to pay fees. There are clear rate structures, which you can check in the official explanation: Simply put, except for school and public service payments which have a 0% rate, other industries have rates between 0.2% and 1%, with 0.6% being the most common.

You might ask, why not just use methods 1 and 2 then?

Unfortunately, that's not feasible. If it's just a small business, a sole proprietorship - or not even registered as one - using methods 1 and 2 to collect small amounts is fine. But as soon as you've registered a company, you can only use method 3. In today's business environment, most things we buy, meals we eat out, food deliveries, and courier services all use method 3.

In other words, when you go out and spend 100 yuan on a meal, the restaurant receives 99.4 yuan, and WeChat takes 0.6 yuan.

Some might think WeChat is making easy money, but in reality, most of this money goes to the banks. Why? As mentioned earlier, WeChat can't directly manage money; it has to be held in custody by banks, and operating bank account funds incurs fees... For example, if paying for a meal goes through UnionPay's bank card, that transaction requires paying about 0.6% in fees to UnionPay.

A look overseas

Recently, there was news about some universities being unhappy with WeChat's 0.6% fee, so WeChat lowered the fee for educational institutions to 0%... In fact, compared to overseas, China's payment fees are quite low.

Taking Visa and Mastercard as examples, when using their cards for consumption, merchants have to pay around 1% to 3% in transaction fees. Calculating at 1.75%, if you go out and spend $100 on a meal, the restaurant receives $98.25.

Question 1: If it's so expensive, why do merchants still use it?

Good question. There are several situations:

- Indeed, many shops only accept cash. This is common in small restaurants in the US and Japan.

- Supporting credit cards might bring additional customers to the shop. For example, many tourist spots display "accept Visa" signs to attract tourists. Tourists might not have enough cash, but they're sure to have credit cards.

- It can reduce some operational costs. For example, some online services, if not using card channels, might need to send bills requesting wire transfers or checks - this is very troublesome and has high operational costs, so they'd rather pay 1.75%.

Question 2: If it's so expensive, why do consumers still use it?

Although it seems that using credit cards for consumption has higher costs, and these costs are passed on to consumers by merchants, as part of the game, if played well, the costs aren't that high.

For example, in Japan and the US, many credit cards offer cashback or points. For instance, I have cards that offer a constant 1% cashback, and versions that offer 1% points constantly with 4% points in specific situations.

If it's 1% cashback, then the actual credit card cost is reduced to 0.75%, which is similar to WeChat. Of course, if it's points and the points expire without being used, that's extra profit for the bank.

Question 3: If paying cash and using a credit card cost the same, aren't cash payers losing out?

Yes, it's as if cash payers are paying a premium - which is another reason to use cards.

High costs of internet payments

Because credit cards are an unavoidable part of US consumer finance, internet financial services like PayPal and Stripe find it very difficult to lower their rates - rates below 1% like WeChat Pay are almost impossible.

PayPal

PayPal is a well-known payment settlement provider with complex fees, details of which can be found in their documentation. It provides both account-to-account transfers (like WeChat Wallet transfers) and merchant settlements (similar to WeChat Pay).

For personal transfers within the US, it's likely free; for international transfers, there's a 5% fee. This means if I'm in Japan and you're in the US, and you transfer me $10, I'll receive $9.50, with PayPal taking 5%.

For corresponding merchant payment settlements, similar to "WeChat Pay" scenarios where a shop receives payments, the rate is usually around 3%. There are additional currency conversion fees for cross-currency transactions.

This means if you buy something online, with the customer in the US and the merchant in Japan, for a $10 item paid through PayPal, the shop will receive about $9.60, which converts to 1395 yen, equivalent to $9.29 at Google's exchange rate.

Stripe

Stripe is a settlement provider used by many overseas merchants, similar to WeChat Pay. Its settlement fees vary by country, for example, 2.9% + $0.30 in the US, 3.6% in Japan - but there are also additional consumption taxes and currency conversion fees.

For example, in Japan, if using Stripe to receive $10, it first converts to about 1471 yen; then Stripe will charge 53 yen as a settlement fee, and at the end of the month, will charge an additional 10% of this, which is 5 yen, as consumption tax.

This means if you buy clothes online, for a $10 order, the Japanese merchant receives about 1471-53-5=1413 yen, which is equivalent to $9.41 at Google's exchange rate.

Trade-offs

Local payments are usually cheaper, which is obvious.

For example, using the JCB channel in Japan instead of Visa, their transaction processing fee is just 0.6% to 1.6%; similarly, if using PayPay in Japan instead of PayPal and Stripe, the rate can be reduced to 1.6% to 1.98%.

It's cheaper, but what's the trade-off?

JCB and PayPay can almost only serve the Japanese domestic market. It's almost impossible to expect foreign tourists to use JCB credit cards in Japan or foreign customers to use PayPay to buy Japanese online comics.

For merchants, if they only serve local customers, of course they can use domestic payment services. But if they want to serve globally, it also means they have to pay the corresponding price.

This is the result of the trade-off mentioned at the beginning.

Taxes

In most countries, there's another big chunk for each transaction: tax. For example, Japan's consumption tax is defaulted at 10%, Germany's is 19%, and Poland's is 23%.

Going back to our example, if a merchant sells something online for $10, if this merchant is registered in Japan, the customer actually needs to pay $11; if registered in Germany, they need to pay $11.9; if registered in Poland, they need to pay $12.3.

So we get the tax-inclusive price, $11 (Japan) or $11.9 (Germany) or $12.3 (Poland).

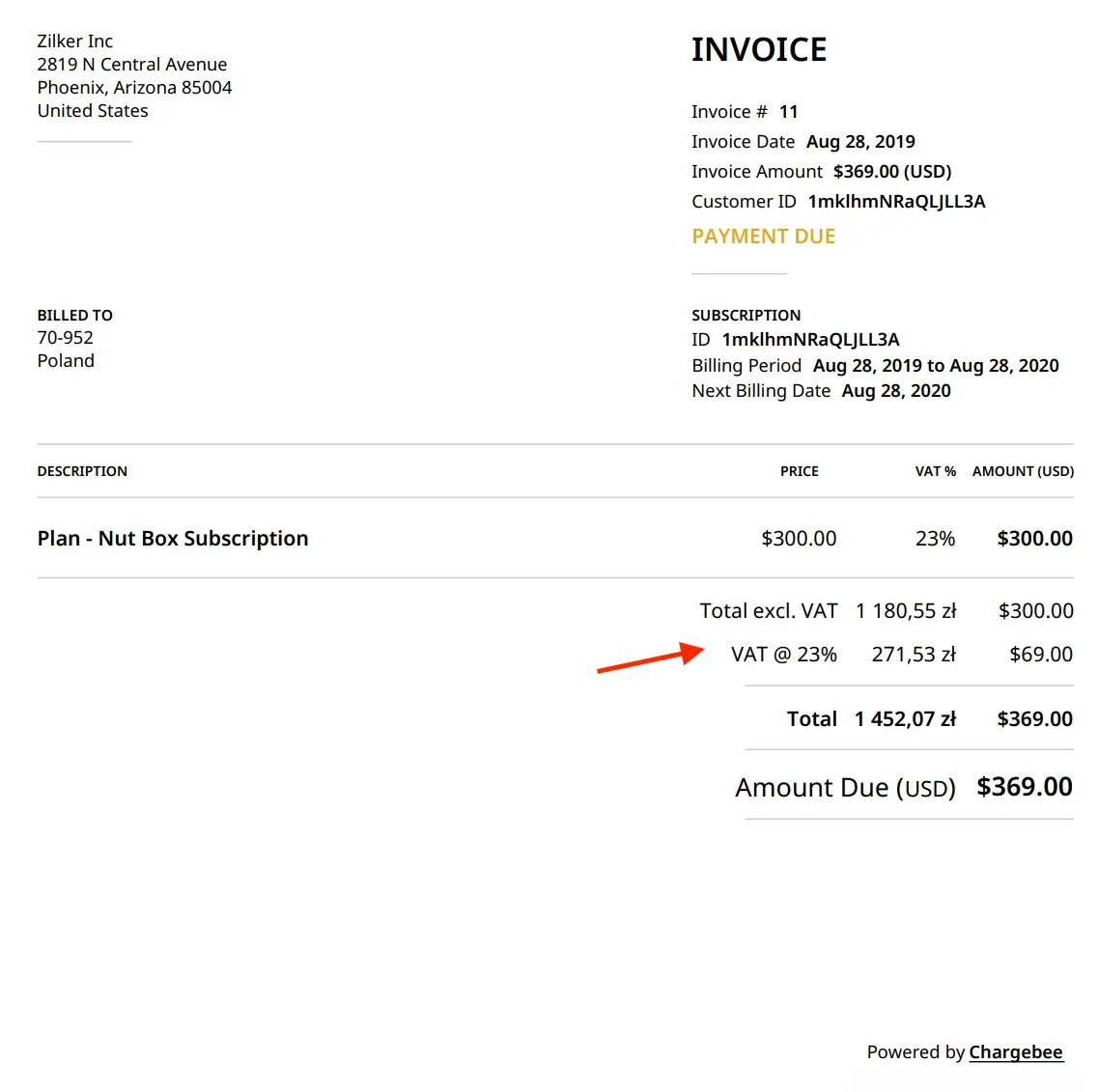

In most countries, both the tax-inclusive and tax-exclusive prices are required to be shown to customers. So abroad we can see receipts like this:

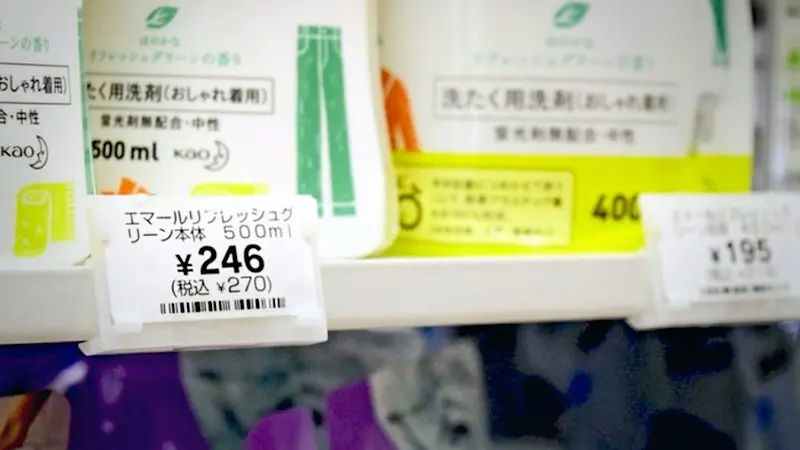

Or labels like this:

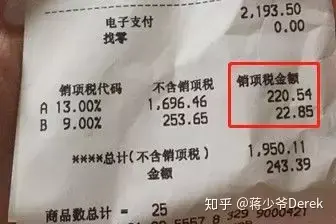

China also has VAT, with rates of 6%, 9%, and 13%. When Sam's Club first opened, they also printed it on the receipt, like this:

But later, to reduce the shock to the public, like other merchants, they stopped printing it on the receipt. However, not printing it doesn't mean it's not there, it just changed from a visible fee to an invisible one.