The Rift Between Geography and Culture

We often forget that both China and the United States are vast countries, making it difficult for just 'one voice' to exist.

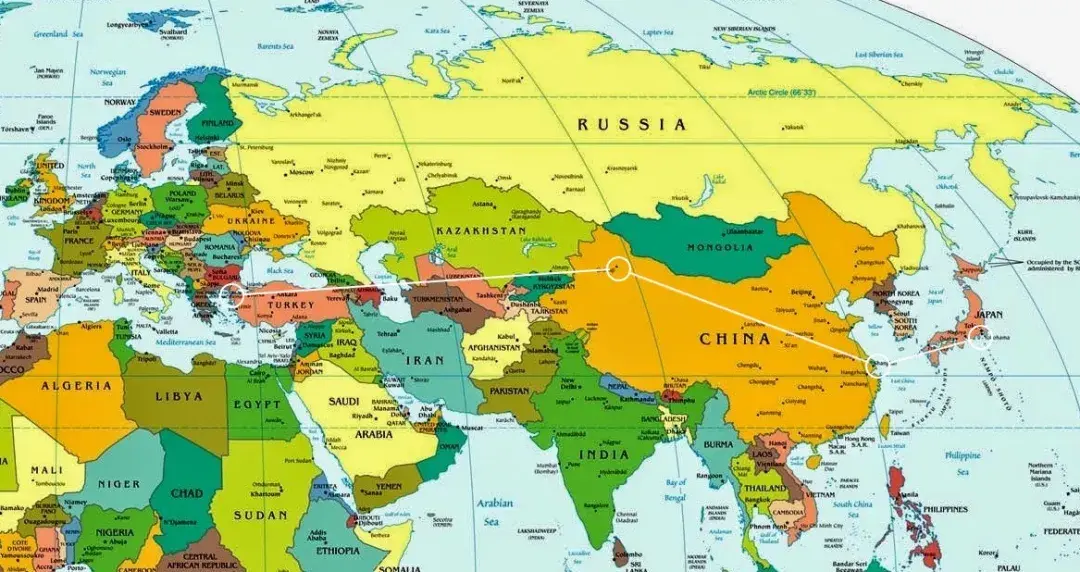

Consider the distances: Shanghai to Tokyo is over 1,700 km, but Shanghai to Urumqi is 4,300 km. Urumqi to Istanbul is only slightly further, at 4,730 km.

To someone from Shanghai, the cultural distance to Urumqi might feel greater than that to Tokyo.

Similarly, Muslims in Xinjiang might feel a closer affinity to Istanbul than to Shanghai.

Cultural differences manifest in more than just language.

The cultural differences between provinces can be as significant as those between nations—perhaps even more so when compared to the relatively smaller countries of Europe.

Tier-one cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, ordinary provincial capitals, and towns in the fifth or sixth tier are almost like countries at three distinct stages of development, each with vastly different cultures.

This also explains the phenomenon of "always arguing when returning home for Spring Festival": it's essentially like international travel.

Respect: A Two-Way Street

I spent a few years in Tokyo.

The older generation often asked me: Do the Japanese discriminate against Chinese people?

My counter: Do Shanghainese discriminate against people from Henan?

It's a reality that foreigners face varying difficulties when renting in Japan. Landlords review potential tenants' backgrounds, including nationality, employment, income level, history of defaults, and so on.

It's true that some landlords are particularly strict with Chinese nationals.

Taken at face value, this looks like discrimination against the Chinese.

But much discrimination doesn't arise from nowhere; it's often a response to the perceived probability of negative outcomes – what businesses call 'risk control'.

Someone asked Linux founder Linus Torvalds why he cursed people out on mailing lists. He replied:

I only respect people who deserve respect. Some people think respect must be given, but I'm one of those who disagree with that view. Respect has to be earned. If you don't earn it, you won't get it. It's that simple.

So, I think the answer is simple:

If Chinese people living abroad wish to be respected by others, they need to earn that respect.

This respect, however, is for you as an individual. Only then might you have a chance to change the perceived risk probabilities associated with your group.

What is truly stubborn, however, is institutionalized discrimination: in areas like the hukou system, housing, education, healthcare, and gender.

Pride in Identity vs. Pride in Contribution

Growing up in China, you're taught from a young age to be proud of being Chinese.

This strikes me as odd.

China is indeed an ancient civilization with a long and culturally rich history. Chinese people, past and present, have made magnificent contributions.

But what do these achievements have to do with me? I neither created them nor participated in them.

If I derive my self-worth from belonging to a group, it merely suggests I have nothing to offer as an individual and must rely on collective identity. That holds no real meaning for the individual.

If I am to feel pride, it should stem from my own contributions and achievements – things I've done, ways I've helped others – not from something I was born with.

'Being Chinese' is fundamentally like 'having naturally double eyelids' or 'having a predisposition to diabetes' – they are inherent traits. No one feels proud of having double eyelids or being prone to diabetes, right? So why take pride in your nationality?

Logically, this presents a paradox.

The Scale of Energy

A few years ago, I interviewed an engineer.

During the post-interview chat, the topic of BTC came up. He criticized Bitcoin for its high electricity consumption, noting its annual usage approached that of the Three Gorges Dam, calling it wasteful.

He was correct about the order of magnitude. The Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index estimates BTC's annual electricity consumption at around 77 TWh. The Wikipedia page for the Three Gorges Dam lists its approximate annual output as 100 TWh – indeed, the same order of magnitude.

My explanation at the time was that Proof-of-Work (POW) is inherently energy-intensive, hence the research into alternatives like Proof-of-Stake (POS) and Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPOS).

Later, though, I reconsidered. So what if it's POW? Why feel the need to justify it?

Is there really a problem with a global payment network requiring the equivalent annual output of a massive hydroelectric dam to function?

Human energy consumption is bound to rise; it would be strange if it didn't.

Many science fiction stories feature interstellar travel and planetary development; reaching for the stars requires vast amounts of energy.

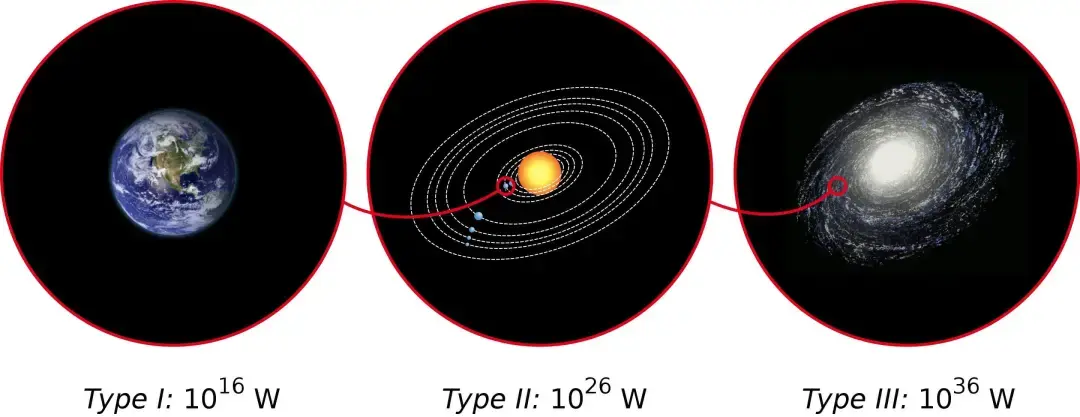

In 1964, Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev proposed classifying civilizations based on their energy consumption, known as the Kardashev Scale:

- Type I Civilization: Harnesses the total energy of its home planet, consuming energy on the order of 10^16 W.

- Type II Civilization: Harnesses the energy of its host star, consuming energy on the order of 10^26 W.

- Type III Civilization: Harnesses the energy of its entire galaxy, consuming energy on the order of 10^37 W.

Currently, humanity hasn't reached Type I.

In 2018, global energy consumption was approximately 18 TW, merely 10^13 W.

That's still three orders of magnitude short of Type I.

If we genuinely aim for the stars, dedicating a millionth of our energy budget to maintaining a global financial system will eventually seem rather frugal.

The greatest challenge is our short lifespan – perhaps only 50 years of effective rational thought. Placed against the history of civilization, it's merely an instant.

We perceive ourselves on level ground because our sight extends only a few meters; we might be at the bottom of a valley, or perhaps already atop a summit.