When I first arrived in Japan, I heard a joke:

A Japanese boss was shipping goods to China. Before sending them out, he instructed his worker not to use discarded newspapers for wrapping the items.

The worker asked why.

He explained that the newspapers were covered in Chinese characters, which Chinese people could read. If we wrap things in these newspapers, and the writings on them get read by people in China, it might harm our Chinese customers.

Chinese people can indeed understand many Japanese kanji, but this Japanese boss also had a good understanding of China.

Being able to read Chinese characters really helps with learning Japanese. I found it odd that my first Japanese language textbook didn't have any kanji in it. It turned out, my teacher explained, that this textbook was designed with "students from western countries" in mind, hence the absence of kanji—I understood immediately.

Although Japan had its own language, it didn't have a writing system initially. Therefore, as Buddhism was introduced from China to Japan, the earliest Buddhist monks adopted Chinese characters as the earliest writing system for Japanese.

However, since Chinese and Japanese do not belong to the same language family, the invention of "kana" later on led to the formation of the initial Japanese writing system with both kanji and kana. Subsequently, "hiragana" evolved to spell various conjugations and Japanese vocabulary. Around the same time, "katakana" was derived from parts of Chinese characters by monks, originally used to annotate the pronunciation of Chinese characters.

Later on, Japanese vocabulary gradually became standardized, roughly divided into three categories:

- Wago

- Kango

- Gairaigo

Wago refers to vocabulary originally in Japanese, spelled with hiragana. For example: おはよう (good morning), わたし (I, me, myself), が (a particle), etc.

Kango includes words imported from China in ancient times, like "世界" (world), "学問" (scholarship), "親切" (kindness); and others later created using Chinese characters, like "電話" (telephone), "文化" (culture), "安全" (safety), etc.

Gairaigo mainly comprises words from English, with a smaller portion from other languages (including modern Chinese). For example, コンビニ (convenience store) is a transliteration of the "conveni" from English "convenient store"; パソコン (computer) is an abbreviation of "personal computer" (yes, it’s odd like that). They are mostly spelled with katakana.

Thus, foreign words are often used to express newly emerging concepts and items. Even things that already have Japanese or Chinese names might be re-expressed with foreign words. For example, "めし" (meal), "ご飯" (rice), and "ライス" (rice, from English "rice") all refer to the same thing.

However, these foreign words and native words have subtle differences in meaning and nuance. For instance, both "牛乳" and "ミルク" (milk) refer to milk, but "煙草" is commonly known as "タバコ" (tobacco) in the retail industry. "おさけ, ワイン, アルコール" all mean alcohol, but "おさけ" usually refers to Japanese sake, "ワイン" to wine, especially from grapes, and "アルコール" is a general term for alcohol.

Overall, Chinese gives an impression of formality and seriousness, while foreign words bring a sense of novelty.

Even many foreign words have become somewhat disconnected from their original languages. For those originating from English, they are referred to as "Wasei-eigo" (Japanese-made English). For example, "panelist" should be written as "パネリスト", but "パネラー" was coined, expressing the same meaning, though no such word exists in English.

In casual speech, some non-foreign words are also abbreviated and spelled with katakana, like "キモい" for "disgusting", which is a short form of "気持ち悪い (kimochi warui)".

Thus, it's a common phenomenon among young people to use foreign words (or pseudo-foreign words). Whether or not it's an English word, as long as it's cool, that's all that matters.

This phenomenon also occurs in Chinese. For example, "笔记本" (notebook) -> "电脑" (computer) -> "本儿" (in Northeastern dialect) -> "mbp". Or "厉害" (awesome) -> "永远的

神" (forever god) -> "YYDS".

In everyday writing and expression, sentences often intermix kanji, kana, and punctuation "、". For example:

暑いと、プールへ行きたい (It's hot, I want to go to the pool)

This sentence is easy to read because you can quickly identify 暑い、と、プール、へ、行きたい. If it were all in kana, it would be difficult to read:

あついとぷーるへいきたい (It's hot, want to go to pool)

It feels like how Chinese people look at pure pinyin.

Regarding foreign words, I want to add a bit more.

There was a picture online intended to show the evil of katakana:

In reality, it's not that bizarre; this image is a bit exaggerated for the sake of criticism. If you visit Qiita.com, a website for programmers, you'll find that English is still used directly when appropriate:

Python is just Python, not "パイソン". Raspberry is not "ラズベリー".

It seems that Japanese programmers share my view: industry terms are better off in English.

However, I feel that there's a bit of an overuse of katakana in Japanese now, but I also understand why. When new vocabulary enters Japan and there's no suitable existing word (kanji combination) to express it, using katakana is indeed one approach—after all, not everyone speaks English—but, it's kind of a lazy approach. I still miss the era when Japanese scholars translated foreign words with kanji.

Although a large amount of Japanese vocabulary comes from China, cultural exchange is bidirectional. Thus, in modern times, a significant number of "Wasei-kango" (Japanese-made Chinese words) have been transmitted back to China, becoming part of modern Chinese.

These words can be further categorized into three types:

- Words that originally existed in Chinese but gained new meanings in Japan, like "電気" (electricity), "電報" (telegram), "地球" (earth), "銀行" (bank), "化学" (chemistry), "直径" (diameter), "風琴" (organ), "料理" (cuisine).

- Words that Japan used ancient Chinese terms to translate other foreign words, like "革命" (revolution), "文化" (culture), "観念" (concept), "福祉" (welfare), "文明" (civilization).

- New words created in Japan and then introduced to China, like "電話" (telephone), "情報" (information), "科学" (science), "哲学" (philosophy), "喜劇" (comedy), "美学" (aesthetics), "神経" (nerve), "軟骨" (cartilage).

A typical example of the first category is "銀行" (bank):

In Chinese, the original meaning of "銀行" was a shop selling precious metals and jewelry:

银行 [Yinhang], now called Yinhang Street in Jinling, where goods were gathered; Hua Row, now called Layer Tower Street, also called Hua Row Street, where flowers were made. The markets exist in name only, not in trade.

—《Ji Qing Xu Zhi》

However, in 1851, when the American missionary Pei Zhiwen's "A Brief History of the Great American Federation" was introduced and reprinted in Japan, published in Tokyo in 1864, it mentioned:

The various taxes collected in the state amount to several hundred million silver annually, for example, the bank collects sixty million silver in taxes each year. As for civilian banks in the capital, they currently have about thirty-five million in capital.

Here, the bank already has its modern meaning of "bank". Thus, the modern Chinese term "银行" originally was a Chinese word, but its most widespread modern meaning comes from the Japanese "銀行".

At the time these Chinese terms from Japan entered China, in fact, many people opposed them. For example, scholar Peng Wenzu thought "取缔" should be changed to "禁止", "场合" to "时、事、处", "第三者" to "他人", "动员令" to "动兵令", "打消" to "废止", "

目的" to "主眼", "取消" to "去销", "手续" to "次序", etc.

Unfortunately, these resistances were not effective, and the above-mentioned Wasei-kango have all entered modern Chinese. So, dear readers, a large part of your everyday speech uses Japanese words.

Many people mistakenly believe that places outside mainland China use traditional characters, but this is not correct (even the "traditional characters" vary by region). Japan simplified many kanji after 1946. Some simplifications are identical to those in Simplified Chinese, like the "国" in "国家" (country) (Unicode: U+56FD)

However, some are completely different in terms of writing and Unicode encoding, like the "变" in "变更" (change) (U+53D8) is written as "変更" with "変" (U+5909) in Japanese kanji.

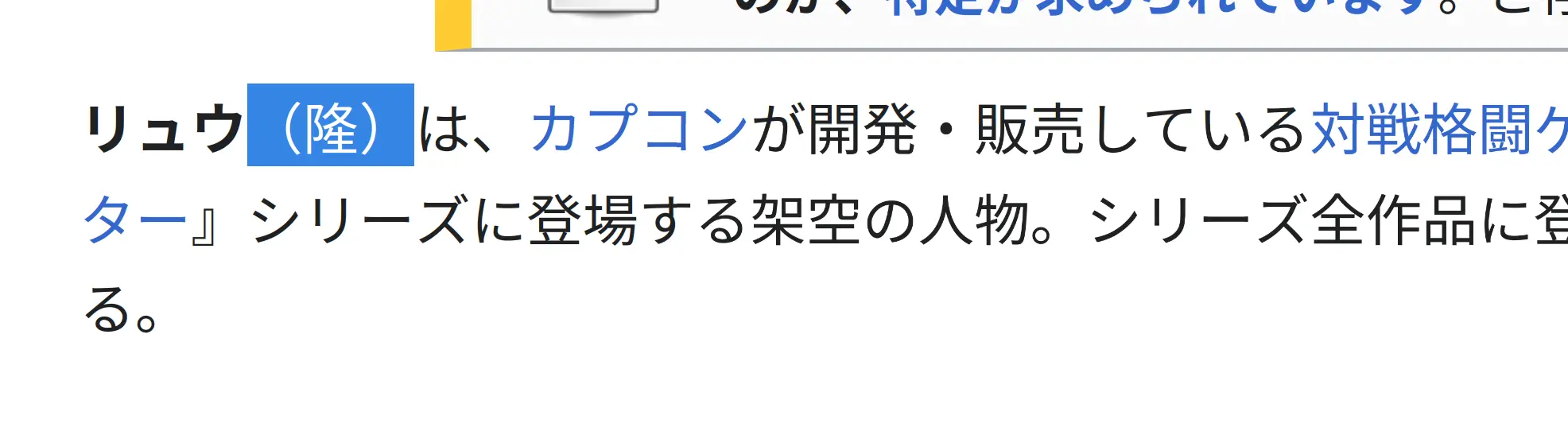

Some characters, although having the same Unicode encoding, display differently in different fonts due to regional simplifications. For example, "生意兴隆" (business booming) "隆" has the Unicode U+9686, but it appears as "隆" in Chinese fonts and as follows in Japanese fonts:

Ah, right, it's missing a stroke. You can visit the webpage RYU (隆) on a system that supports Japanese (like iOS) to see how "Ryu" from "Street Fighter" is written.