良好的饮食习惯会影响你的运动表现和恢复能力。所有运动员都明白这一点。

但究竟有多少人真正知道自己该吃些什么呢?

自行车运动员的营养,尤其是如何选择合适的补给品,可能并不像你想象的那么简单。

在这篇文章中,我们将为你提供所有关键信息,帮助你做出正确选择(再也不用担心突然断糖啦)!

疲劳的一个决定因素

在耐力活动中,导致疲劳的一个主要因素就是糖原的耗竭。

糖原是人体内葡萄糖的储备形式。

作为人类,我们储存碳水化合物为糖原的能力是有限的,通常肌肉中储存约 400 克,肝脏中储存约 100 克。这些加起来总共不到 3000 千卡,其中约 80%储存在肌肉中,约 10%到 15%储存在肝脏中(Gonzalez, Javier T 等,2016)。

假设以高度训练的长跑运动员所观察到的典型跑步经济性数值(1.07 千卡/公斤/公里)(Fletcher, Jared R 等,2009 年)以及体重为 68 公斤来计算,这些体内储存的碳水化合物根本不足以支撑哪怕一场马拉松比赛(约 3070 千卡)……

糖原的储存受一种酶——糖原合酶(GS)的调控。

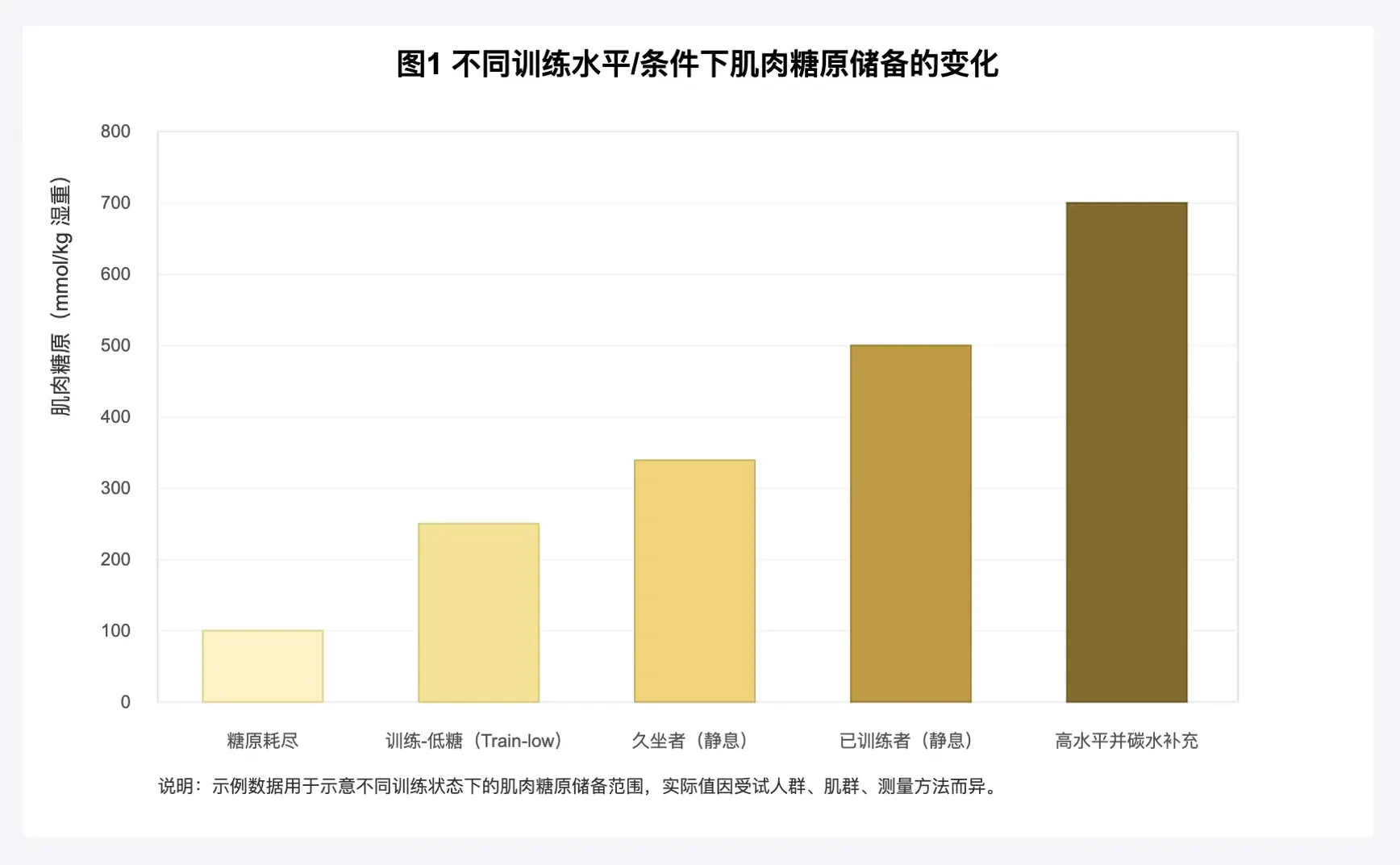

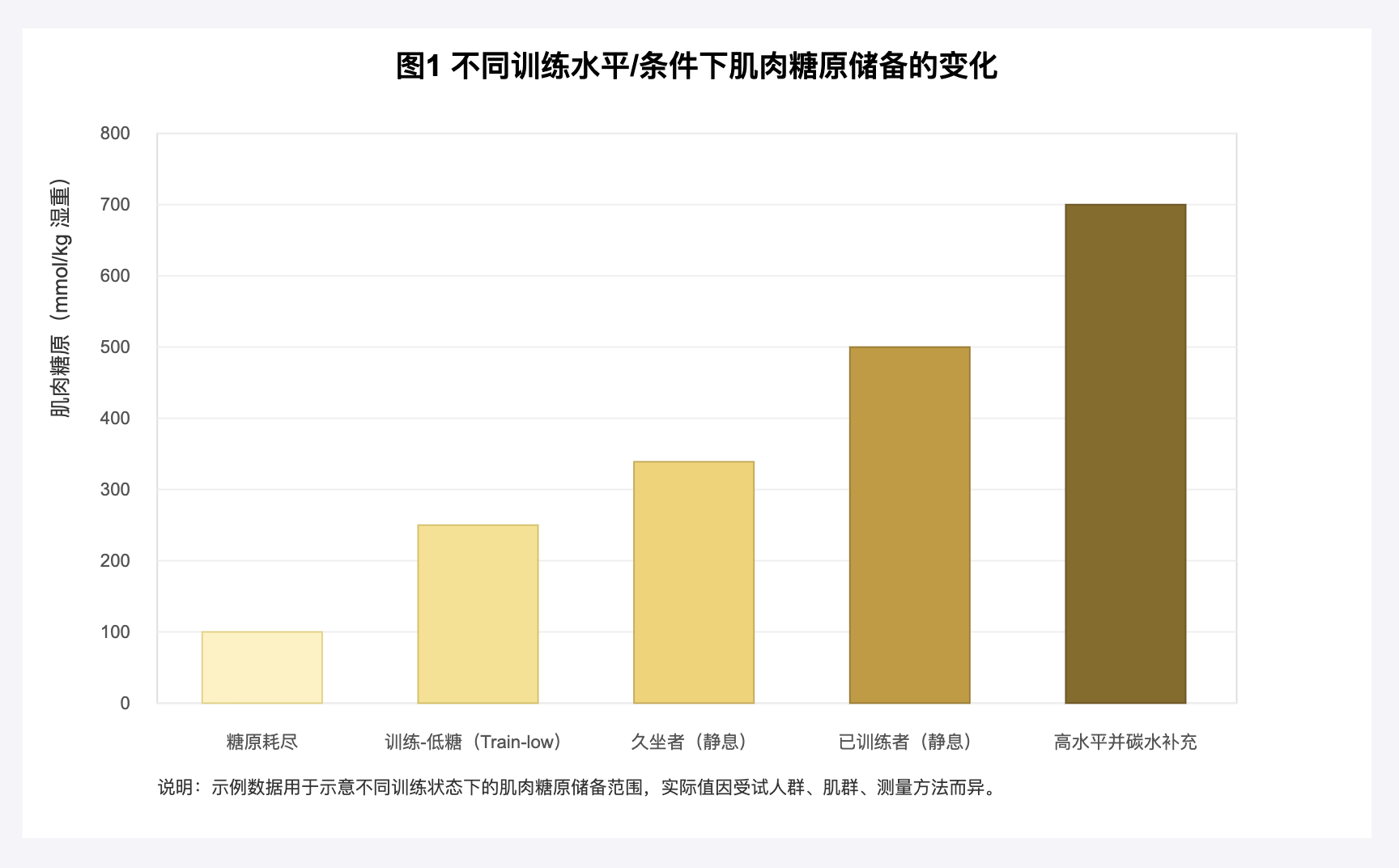

鉴于糖原在运动表现中发挥着重要作用,训练有素的人能够储存更多的糖原(图 1)(Taylor 等,2013;Bartlett 等,2013;Arkinstall 等,1985;Gollnick 等,1974;Coyle 等,1986)。

图 1。 肌肉糖原储备随训练水平或身体状况的变化

此外,有研究表明,经过训练的运动员肌肉细胞对胰岛素的敏感性更高(Borghouts 和 Keizer,2000),并且体内 GLUT-4 转运蛋白的数量也更多(Greiwe 等,1999)。正是这些适应性变化,能够调节运动后肌肉糖原的再合成。因此,经过训练的运动员在运动后也能更快地完成肌肉糖原的再合成。

Hickner 等(1997)比较了训练组(VO 2 peak:59.6 mL/kg/min)与未训练组(VO 2 peak:38.3 mL/kg/min)的肌肉糖原再合成情况。他们发现,在停止运动 72 小时后,训练组的肌肉糖原浓度是未训练组的两倍。这一现象可归因于训练组更高的糖原再合成速度,以及其体内 GLUT-4 转运蛋白含量是未训练组的三倍,从而更有利于葡萄糖的摄取。

减少疲劳

如果肌肉糖原是导致疲劳的主要因素之一,那么在运动过程中维持或减少肌肉糖原的消耗,将有助于提高运动表现,并延缓疲劳的出现。

这正是运动期间摄入碳水化合物所能实现的效果:它能够减少我们体内自身碳水化合物储备的消耗。

运动期间摄入碳水化合物能够延缓疲劳的产生(Coggan 和 Coyle,1987),并提升运动表现(Jeukendrup,2004;Vandenbogaerde 和 Hopkins,2011)。

运动期间补充外源性碳水化合物,有助于维持血浆葡萄糖的供应,特别是在糖原储备耗竭并对长时间运动形成限制时(Coyle 等,1986)。此外,它还能保持血糖水平的稳定,从而有效预防低血糖的风险(Coggan 和 Coyle,1987)。

保持血糖稳定有助于减少肝脏产生葡萄糖的需求。补充外源性碳水化合物可以节省肝糖原,同时为肌肉提供充足的碳水化合物供应。肝脏中的糖原可以得到完全的保存,而肌肉中的糖原则无论如何都会耗尽,只不过通过补给碳水化合物,其消耗速度会有所减缓(Bosch, A N 等 ,1994;Jeukendrup, A E 等 ,1999;Gonzalez, Javier T 等 ,2015;Jeukendrup, A E 等 ,1999)。

运动中摄入碳水化合物的理念并非新鲜事物。事实上,这一观点很早就由 D. Costill 的研究团队提出(Ivy 等,1979;Fielding 等,1985)。但直到现在,我们才逐渐摸索出最佳的碳水化合物摄入剂量和形式。

自行车运动员的实际营养策略

选择最佳剂量

在运动过程中摄入多少碳水化合物,并非随意决定。

在训练或比赛过程中,碳水化合物的摄入策略应根据比赛的持续时间和具体条件(如环境条件、比赛难度等)、运动中补给的可能性以及比赛策略等因素来决定。每种策略都需根据每位运动员的具体情况量身定制,包括其个人历史、赛前超量恢复策略(如赛前训练负荷、赛前几天增加碳水化合物摄入等)以及消化能力等。

最佳的碳水化合物摄入量是指能够使外源性碳水化合物氧化率达到最大值的摄入量(Jeukendrup 和 Jentjens,2000)。

超过一定量后,由于外源性碳水化合物的氧化率已达到上限,出现消化道不适的风险将显著增加。此外,根据比赛强度的不同,并非总是需要尽可能多地补充碳水化合物。

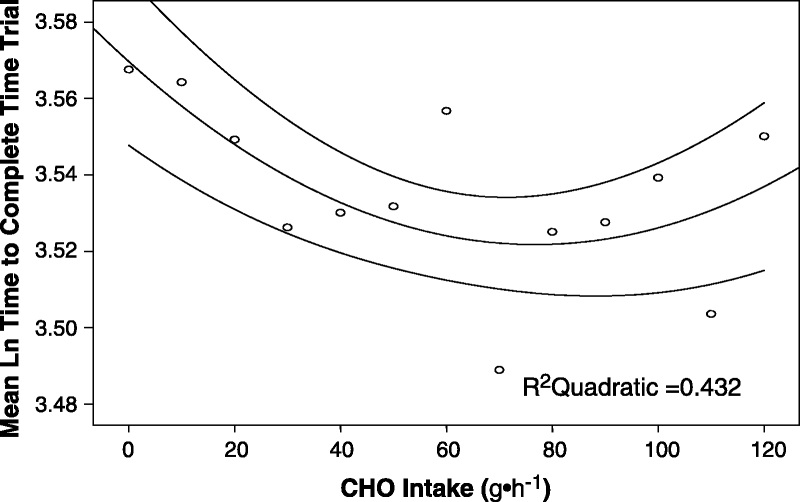

图 3。 运动持续时间与碳水化合物摄入量之间的关系。摘自 Smith 等人,2013

Smith 等人研究了碳水化合物摄入量与运动表现之间的关系(图 3)。

在他们的研究中,51 名自行车运动员和铁人三项运动员接受了持续 2 小时、强度为乳酸阈值 95%(4 mmol/L)的运动。因此,他们的运动强度位于第三区的高端,处于与第四区的过渡地带(采用 6 区或 7 区划分模式)。他们每 15 分钟需摄入 250 毫升液体,这种液体要么是安慰剂饮料,要么是由 1%至 12%的碳水化合物(葡萄糖与果糖比例为 2:1)以及电解质(钠 18 mmol/L、钾 3 mmol/L、氯 11 mmol/L)组成的饮料。紧接着,他们还需进行一项 20 公里的计时赛作为运动表现测试,期间不得再摄入任何碳水化合物。

结果显示,当碳水化合物摄入量分别为 9 克/小时、19 克/小时、31 克/小时、48 克/小时和 78 克/小时时,运动表现分别提高了 1%、2%、3%、4%和 4.7%(Smith 等,2013)。在这种情况下(运动时间少于 3 小时),摄入超过 78 克/小时似乎并不能进一步提升运动表现。

比赛中的最佳剂量

因此,对于持续时间超过 90 分钟的运动,建议每小时摄入 30 至 60 克碳水化合物(0.5 至 1 克/公斤/小时)(美国营养与膳食学会、加拿大注册营养师协会,2016 年)。而对于持续时间超过 3 小时的运动,摄入量应达到每小时 60 至 90 克,若运动强度极高,甚至可超过每小时 90 克(Jeukendrup,2014;美国营养与膳食学会、加拿大注册营养师协会,2016 年)。

最近,Aitor Viribay (Glut 4 science 创始人兼 INEOS 车队营养师)发表了一项研究,测试了在一场正爬升高度达 4000 米、时长 4 至 5 小时的越野跑比赛中,跑者分别采用每小时 60 克、90 克或 120 克碳水化合物的补给策略。

120 克/小时的策略有助于减少肌肉损伤,并降低对运动难度的感知(维里拜、艾托尔等,2020 年)。

限制肌肉损伤有助于实现更佳的恢复 。

因此,每小时摄入大量碳水化合物不仅能够提升运动表现,还能促进更好的恢复。

一小时以内比赛的最佳剂量

对于一小时以内的比赛,尤其是计时赛,研究表明,在一小时的运动过程中摄入碳水化合物可以提高运动表现(Below 等,1995;Jeukendrup 等,1997)。而如果在 30 分钟的计时赛前 15 分钟摄入 40 克碳水化合物,则不会对运动表现产生显著影响(Palmer 等,1998)。

因此,外源性碳水化合物的补充能够在运动持续时间接近 60 分钟时改善运动表现(Jeukendrup, A 等,1997),尽管在这种运动时长下,肌肉和肝脏中糖原的储备可能并不构成限制因素。

那么,如果糖原储备并非限制因素,外源性碳水化合物的摄入为何还能提高运动表现呢?

碳水化合物对中枢神经系统的影响

要确定外源性碳水化合物摄入的效果是否纯粹是代谢性的,就必须绕过口腔中的碳水化合物感受器,这些感受器可能会激活大脑中的某些区域。实现这一目标的最佳方法,就是直接将葡萄糖输注到血液循环中,从而跳过口腔这一环节。

结果发现,当给自行车运动员直接输注葡萄糖或安慰剂溶液时,在一小时的计时赛中表现并未得到改善(Carter, James M 等人,2004)。因此,外源性碳水化合物摄入的效果并非“代谢性”的。

那么,这种效果可能直接作用于中枢神经系统。为了验证这一假设,多项研究测试了仅仅用碳水化合物溶液漱口是否足以提升运动表现。

- Carter 等人研究表明,持续 5 秒的漱口可提高一小时计时赛的表现(Carter, James M 等,2004)。

- Phillips 等人研究表明,持续 5 秒的一系列漱口动作可提高 30 秒冲刺的表现(Phillips 等,2014)。

用富含碳水化合物的溶液漱口

因此,对于持续时间不足一小时的高强度运动,仅通过漱口便足以提升运动表现(Burke 等,2015)。

用富含碳水化合物的溶液漱口会刺激口腔内的碳水化合物受体(T 1 R 2 和 T 1 R 3 型 G 蛋白偶联受体蛋白),从而激活与动机和步速相关的大脑区域(Rollo 和 Williams,2011)。此外,漱口还能降低对运动强度的感知。这种效果与甜味无关(Chambers, E S 等,2009)。

空腹状态下以及肌肉糖原储备耗竭时,漱口的效果尤为显著(Lane, Stephen C 等,2013),并且在这一情况下,漱口的效果并非总是能够得到证实(Ali, Ajmol 等,2016)。

实际上,漱口可能有所帮助:

- 在计时赛出发前(如果计时赛距离较长,中途可以补充一块能量胶)

- 例如在“睡眠低糖”训练方案中进行空腹训练时

训练中的最佳剂量

在训练过程中,摄入适量的碳水化合物同样重要:耐力型骑行超过 2 小时 30 分钟时,每小时至少应摄入 60 克;高强度骑行超过 2 小时时,则每小时至少应摄入 70 克。摄入碳水化合物会影响身体优先氧化的底物类型,若碳水化合物摄入量增加,自然会减少脂肪的氧化比例。 尽管如此,碳水化合物的摄入并不会妨碍线粒体生物发生相关的细胞信号通路(Fell, J Marc 等,2021;Lee-Young, Robert S 等,2006)。因此,与完全不摄入碳水化合物的训练相比,这种训练方式所引发的身体适应性变化基本相同,只不过通过补充碳水化合物,你的恢复会更好,而且运动时也会感觉更加轻松!

存在一种替代方法

一种有助于保存糖原储备的替代方法,是通过饮食调整和训练方案,促使身体在运动过程中更多地利用脂肪作为燃料。这种方法的优点在于,无需在比赛期间摄入大量外源性碳水化合物,从而降低了出现消化道不适的风险。不过,这种策略更适合用于超长距离耐力赛事的备战,因为它可能会削弱高强度运动的能力。

哪种类型的碳水化合物?

源于车手,为突破而生:鼓轮体育为 PLAN-GIO 胶计划中国总代理

在运动过程中,每小时摄入超过 60 克碳水化合物并不像单纯多吃那么简单……

为了减少胃部不适,研究表明,增加碳水化合物的来源(如葡萄糖、果糖)可能是有益的(O’Brien 等,2011)。

此外,摄入两种不同类型的碳水化合物能够提高碳水化合物的氧化率,并减少糖原的消耗(见图 4)(Jentjens 等,2004),最终有助于提升耐力表现(Currell 和 Jeukendrup,2008)。

事实上,单独摄入葡萄糖或麦芽糊精时,我们的肠道和血液循环似乎每小时只能吸收约 60 克(Hawley, J A 等,1992)。这意味着,如果我们以每小时 60 克、90 克或 120 克的速度摄入葡萄糖,实际上能够用于支持能量代谢的量仍然只有大约每小时 60 克。而未被代谢的部分则会滞留在肠道中(Jeukendrup, A E 等,1999),这可能会引发消化不良等问题。这样的说法只适用业余场景下,职业运动员高碳水摄入已经成为流行。

图 4。 底物对总能量消耗的相对贡献比较:无碳水化合物摄入、葡萄糖摄入、葡萄糖+果糖摄入

这种效应之所以能够实现,是因为葡萄糖和果糖通过不同的转运蛋白进入细胞。葡萄糖的摄取依赖于钠离子依赖性葡萄糖协同转运蛋白 1(SGLT 1),而果糖则通过 GLUT 5 转运。此外,GLUT 2 能够同时转运这两种分子(Wilson,2015)。

图 5. 葡萄糖和果糖的转运蛋白

因此,增加碳水化合物的来源可以避免某一载体负担过重,而是将工作量分散到不同的载体上(图 5)。

事实上,在葡萄糖浓度较高(>50-60 克/小时)的条件下,SGLT 1 会达到饱和状态,从而限制了肠道对葡萄糖的吸收,并减缓了胃排空。肠道吸收是限制碳水化合物氧化的关键因素(Duchman 等人,1997)。

此外,葡萄糖会促进果糖的摄取(Tappy 和 Lê,2010)。

因此,对于持续 2.5 至 3 小时的耐力运动而言,最佳比例似乎是每 1 份葡萄糖搭配 0.5 至 1 份果糖(Rowlands 等,2015)。

也就是葡萄糖:果糖 = 2:1

以何种形式?

运动时摄入碳水化合物的方式多种多样:运动饮料、能量胶、能量棒……究竟该选哪一种呢?

凝胶与能量棒的对比

能量棒或凝胶的优点在于,它们能够迅速提供大量碳水化合物,而无需饮用大量液体(与运动饮料相比)。

凝胶在实用性上优于能量棒,但能量棒通常在口感上更令人满意。

两者并没有绝对的优劣之分。重要的是你是否喜欢它们的味道和质地,以及补给是否方便(在高强度运动中,摄入凝胶比吃能量棒更容易、更快速)。

不过,你需要注意能量棒的成分搭配,确保其适合你的需求。事实上,这类食品中通常含有的纤维和脂肪应加以限制,以避免引起胃部不适。

同时也要注意新型凝胶/饮料的口味,有时这可能是导致肠胃不适的原因。在比赛前务必试用你的补给品,以确保自己能够耐受。

固体与液体

Pfeiffer 等人比较了以固体或液体形式摄入碳水化合物的有效性。

八名受过训练的受试者需以自身最大摄氧量的 58%强度骑自行车 180 分钟。他们分别摄入一种能量棒搭配水(400 毫升水和 43 克碳水化合物,每根能量棒重 65 克)、一种能量饮料(400 毫升,由 10.75%的葡萄糖和果糖组成)或单纯饮水(400 毫升)。结果表明,两种不同形式的碳水化合物摄入在最大氧化率(能量棒:1.25 ± 0.15 克/分钟;能量饮料:1.34 ± 0.27 克/分钟)和平均氧化率(能量棒:1.03 ± 0.11 克/分钟;能量饮料:1.14 ± 0.16 克/分钟)方面并无显著差异(Pfeiffer 等,2010)。

根据相同的实验方案,Pfeiffer 等人还比较了以凝胶(葡萄糖与果糖比例为 2:1,摄入速率为 108 克/小时)或饮料形式(营养成分相同)摄入碳水化合物时的氧化速率。结果显示,不同形式的碳水化合物摄入对氧化速率并无显著影响(凝胶:1.44 ± 0.29 克/分钟;饮料:1.42 ± 0.23 克/分钟)(Pfeiffer 等,2010)。

因此,以固体或液体形式摄入碳水化合物在效果上并无差异。最好还是多样化摄入来源,但如果你只能选择一种碳水化合物来源,这也不应影响你的表现。

结论

运动员在训练期间往往倾向于限制摄入量,以避免体重增加。这是可能犯下的最大错误之一。

无论是训练还是比赛,补给都必须提前规划好。

在比赛中,如果补给不当,就很可能导致表现失常。

而在训练中,补给不合适会导致强度下降,从而使训练效果大打折扣。此外,还会造成运动后的恢复不良,进而影响接下来的训练。

而且,突然感到饥饿可绝不是什么好滋味……所以最好想尽办法避免这种情况。

如果你想摄入超过每小时 60 克的碳水化合物,就需要进行相应的训练(即肠道适应性训练),并合理选择补给品(果糖与葡萄糖的比例应在 1 到 2之间)。

这不一定非得是凝胶、能量棒和运动饮料。在训练时,也可以选择一些干果(如西梅干、椰枣等,不过要注意纤维含量)、加了糖浆的饮品、水果果泥、自制米饼等。

引用文献

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Dietetitians of Canada (2016) Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:543–568. Doi: 10.1249/MSS. 0000000000000852

Ali, Ajmol et al. “Carbohydrate mouth rinsing has no effect on power output during cycling in a glycogen-reduced state.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition vol. 13 19. 23 Apr. 2016, doi: 10.1186/s 12970-016-0131-1

Arkinstall, M J et al. “Effect of carbohydrate ingestion on metabolism during running and cycling.” Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) vol. 91,5 (2001): 2125-34. Doi: 10.1152/jappl. 2001.91.5.2125

Bartlett, Jonathan D et al. “Reduced carbohydrate availability enhances exercise-induced p 53 signaling in human skeletal muscle: implications for mitochondrial biogenesis.” American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology vol. 304,6 (2013): R 450-8. Doi: 10.1152/ajpregu. 00498.2012

Below PR, Mora-Rodríguez R, González-Alonso J, Coyle EF (1995) Fluid and carbohydrate ingestion independently improve performance during 1 h of intense exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 27:200–210.

Bosch, A N et al. “Influence of carbohydrate ingestion on fuel substrate turnover and oxidation during prolonged exercise.” *Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985)*vol. 76,6 (1994): 2364-72. Doi: 10.1152/jappl. 1994.76.6.2364

Borghouts LB, Keizer HA (2000) Exercise and Insulin Sensitivity: A Review. International Journal of Sports Medicine 21:1–12. Doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8847

Burke, Louise M, and Ronald J Maughan. “The Governor has a sweet tooth – mouth sensing of nutrients to enhance sports performance.” European journal of sport science vol. 15,1 (2015): 29-40. Doi: 10.1080/17461391.2014.971880

Carter, James M et al. “The effect of carbohydrate mouth rinse on 1-h cycle time trial performance.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 36,12 (2004): 2107-11. Doi: 10.1249/01. Mss. 0000147585.65709.6 f

Carter, James M et al. “The effect of glucose infusion on glucose kinetics during a 1-h time trial.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 36,9 (2004): 1543-50. Doi: 10.1249/01. Mss. 0000139892.69410. D 8

Chambers, E S et al. “Carbohydrate sensing in the human mouth: effects on exercise performance and brain activity.” The Journal of physiology vol. 587, Pt 8 (2009): 1779-94. Doi: 10.1113/jphysiol. 2008.164285

Coggan AR, Coyle EF (1987) Reversal of fatigue during prolonged exercise by carbohydrate infusion or ingestion. J Appl Physiol 63:2388–2395.

Coyle EF, Coggan AR, Hemmert MK, Ivy JL (1986) Muscle glycogen utilization during prolonged strenuous exercise when fed carbohydrate. J Appl Physiol 61:165–172.

Coyle, E F et al. “Muscle glycogen utilization during prolonged strenuous exercise when fed carbohydrate.” Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) vol. 61,1 (1986): 165-72. Doi: 10.1152/jappl. 1986.61.1.165

Currell K, Jeukendrup AE (2008) Superior endurance performance with ingestion of multiple transportable carbohydrates. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:275–281. Doi: 10.1249/mss. 0 b 013 e 31815 adf 19

Duchman SM, Ryan AJ, Schedl HP, et al (1997) Upper limit for intestinal absorption of a dilute glucose solution in men at rest. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29:482–488.

Fell, J Marc et al. “Carbohydrate improves exercise capacity but does not affect subcellular lipid droplet morphology, AMPK and p 53 signalling in human skeletal muscle.” The Journal of physiology vol. 599,11 (2021): 2823-2849. Doi: 10.1113/JP 281127

Fielding RA, Costill DL, Fink WJ, et al (1985) Effect of carbohydrate feeding frequencies and dosage on muscle glycogen use during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 17:472–476.

Fletcher, Jared R et al. “Economy of running: beyond the measurement of oxygen uptake.” Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) vol. 107,6 (2009): 1918-22. Doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol. 00307.2009

Gollnick, P.D.; Piehl, K.; Saltin, B. Selective glycogen depletion pattern in human muscle fibres after exercise of varying intensity and at varying pedalling rates. J. Physiol. 1974, 24, 45–57.

Gonzalez, Javier T et al. “Liver glycogen metabolism during and after prolonged endurance-type exercise.” American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolismvol. 311,3 (2016): E 543-53. Doi: 10.1152/ajpendo. 00232.2016

Gonzalez, Javier T et al. “Ingestion of glucose or sucrose prevents liver but not muscle glycogen depletion during prolonged endurance-type exercise in trained cyclists.” American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism vol. 309,12 (2015): E 1032-9. Doi: 10.1152/ajpendo. 00376.2015

Greiwe JS, Hickner RC, Hansen PA, et al (1999) Effects of endurance exercise training on muscle glycogen accumulation in humans. J Appl Physiol 87:222–226.

Hawley, J A et al. “Exogenous carbohydrate oxidation from maltose and glucose ingested during prolonged exercise.” European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology vol. 64,6 (1992): 523-7. Doi: 10.1007/BF 00843762

Hickner RC, Fisher JS, Hansen PA, et al (1997) Muscle glycogen accumulation after endurance exercise in trained and untrained individuals. J Appl Physiol 83:897–903.

Ivy JL, Costill DL, Fink WJ, Lower RW (1979) Influence of caffeine and carbohydrate feedings on endurance performance. Med Sci Sports 11:6–11.

Jentjens RLPG, Moseley L, Waring RH, et al (2004) Oxidation of combined ingestion of glucose and fructose during exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 96:1277–1284. Doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol. 00974.2003

Jeukendrup (2004) Carbohydrate intake during exercise and performance. Nutrition 20:669–677. Doi: 10.1016/j.nut. 2004.04.017

Jeukendrup A (2014) A step towards personalized sports nutrition: carbohydrate intake during exercise. Sports Med 44 Suppl 1: S 25-33. Doi: 10.1007/s 40279-014-0148-z

Jeukendrup A, Brouns F, Wagenmakers AJ, Saris WH (1997) Carbohydrate-electrolyte feedings improve 1 h time trial cycling performance. Int J Sports Med 18:125–129. Doi: 10.1055/s- 2007-972607

Jeukendrup AE, Jentjens R (2000) Oxidation of carbohydrate feedings during prolonged exercise: current thoughts, guidelines and directions for future research. Sports Med 29:407–424.

Jeukendrup, A E et al. “Carbohydrate ingestion can completely suppress endogenous glucose production during exercise.” The American journal of physiology vol. 276,4 (1999): E 672-83. Doi: 10.1152/ajpendo. 1999.276.4. E 672

Jeukendrup, A E et al. “Glucose kinetics during prolonged exercise in highly trained human subjects: effect of glucose ingestion.” The Journal of physiology vol. 515 ( Pt 2), Pt 2 (1999): 579-89. Doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.579 ac.x

Jeukendrup, A et al. “Carbohydrate-electrolyte feedings improve 1 h time trial cycling performance.” International journal of sports medicine vol. 18,2 (1997): 125-9. Doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972607

Kasper, Andreas M et al. “Carbohydrate mouth rinse and caffeine improves high-intensity interval running capacity when carbohydrate restricted.” European journal of sport sciencevol. 16,5 (2016): 560-8. Doi: 10.1080/17461391.2015.1041063

Lane, Stephen C et al. “Effect of a carbohydrate mouth rinse on simulated cycling time-trial performance commenced in a fed or fasted state.” Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme vol. 38,2 (2013): 134-9. Doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0300

Lee-Young, Robert S et al. “Carbohydrate ingestion does not alter skeletal muscle AMPK signaling during exercise in humans.” American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism vol. 291,3 (2006): E 566-73. Doi: 10.1152/ajpendo. 00023.2006

O’Brien, Wendy J, and David S Rowlands. “Fructose-maltodextrin ratio in a carbohydrate-electrolyte solution differentially affects exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rate, gut comfort, and performance.” American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology vol. 300,1 (2011): G 181-9. Doi: 10.1152/ajpgi. 00419.2010

Palmer GS, Clancy MC, Hawley JA, et al (1998) Carbohydrate ingestion immediately before exercise does not improve 20 km time trial performance in well trained cyclists. Int J Sports Med 19:415–418. Doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971938

Pfeiffer, Beate et al. “CHO oxidation from a CHO gel compared with a drink during exercise.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 42,11 (2010): 2038-45. Doi: 10.1249/MSS. 0 b 013 e 3181 e 0 efe 6

Pfeiffer, Beate et al. “Oxidation of solid versus liquid CHO sources during exercise.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 42,11 (2010): 2030-7. Doi: 10.1249/MSS. 0 b 013 e 3181 e 0 efc 9

Phillips SM, Findlay S, Kavaliauskas M, Grant MC (2014) The Influence of Serial Carbohydrate Mouth Rinsing on Power Output during a Cycle Sprint. J Sports Sci Med 13:252–258.

Phillips, Shaun M et al. “The Influence of Serial Carbohydrate Mouth Rinsing on Power Output during a Cycle Sprint.” Journal of sports science & medicine vol. 13,2 252-8. 1 May. 2014

Rollo I, Williams C (2011) Effect of Mouth-Rinsing Carbohydrate Solutions on Endurance Performance. [Review]. Sports Medicine 41:449–461. Doi: 10.2165/11588730-000000000- 00000

Rollo, Ian, and Clyde Williams. “Effect of mouth-rinsing carbohydrate solutions on endurance performance.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 41,6 (2011): 449-61. Doi: 10.2165/11588730-000000000-00000

Rowlands DS, Houltham S, Musa-Veloso K, et al (2015) Fructose-Glucose Composite Carbohydrates and Endurance Performance: Critical Review and Future Perspectives. Sports Med 45:1561– 1576. Doi: 10.1007/s 40279-015-0381-0

Smith JW, Pascoe DD, Passe DH, et al (2013) Curvilinear dose-response relationship of carbohydrate (0-120 g·h (-1)) and performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45:336–341. Doi: 10.1249/MSS. 0 b 013 e 31827205 d 1

Tappy L, Lê K-A (2010) Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. Physiol Rev 90:23–46. Doi: 10.1152/physrev. 00019.2009

Taylor, Conor et al. “Protein ingestion does not impair exercise-induced AMPK signalling when in a glycogen-depleted state: implications for train-low compete-high.” European journal of applied physiology vol. 113,6 (2013): 1457-68. Doi: 10.1007/s 00421-012-2574-7

Vandenbogaerde TJ, Hopkins WG (2011) Effects of acute carbohydrate supplementation on endurance performance: a meta-analysis. Sports Med 41:773–792. Doi: 10.2165/11590520- 000000000-00000

Viribay, Aitor et al. “Effects of 120 g/h of Carbohydrates Intake during a Mountain Marathon on Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage in Elite Runners.” Nutrients vol. 12,5 1367. 11 May. 2020, doi: 10.3390/nu 12051367

Wilson PB (2015) Multiple Transportable Carbohydrates During Exercise: Current Limitations and Directions for Future Research. J Strength Cond Res 29:2056–2070. Doi: 10.1519/JSC. 0000000000000835